The shipwreck of the RMS Rhone is billed as one of the top dive sites in the Caribbean due to the amount of wildlife and the interest of the wreck itself. She was a 310′ passenger and mail liner that sunk in 1867. Due to her excellent performance at weathering other large storms she had been called “unsinkable”. (fun fact: they’re all sinkable..)

On the day of the sinking, Rhone‘s Master, Frederick Woolley, was slightly worried by the dropping barometer and darkening clouds, but because it was October and hurricane season was thought to be over, Rhone and Conway stayed in Great Harbour. The storm which subsequently hit was later known as the San Narciso Hurricane and retrospectively categorised as a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale. The first half of the storm passed without much event or damage, but the ferocity of the storm worried the captains of Conway and Rhone, as their anchors had dragged and they worried that when the storm came back after the eye of the storm had passed over, they would be driven onto the shore of Peter Island.

They decided to transfer the passengers from Conway to the “unsinkable” Rhone; Conway was then to head for Road Harbour and Rhone would make for open sea. As was normal practice at the time, the passengers in Rhone were tied into their beds to prevent them being injured in the stormy seas.

Conway got away before Rhone but was caught by the tail end of the storm, and eventually foundered off the south side of Tortola. But Rhone struggled to get free as her anchor was caught fast. It was ordered to be cut loose, and lies in Great Harbour to this day, with its chain wrapped around the same coral head that trapped it a century and a half ago. Time was now critical, and Captain Woolley decided that it would be best to try to escape to the shelter of open sea by the easiest route, between Black Rock Point of Salt Island and Dead Chest Island. Between those two islands lay Blonde Rock, an underwater reef which was normally a safe depth of 25 feet (7.6 m), but during hurricane swells, there was a risk that Rhone might founder on that. The Captain took a conservative course, giving Blonde Rock (which cannot be seen from the surface) a wide berth.

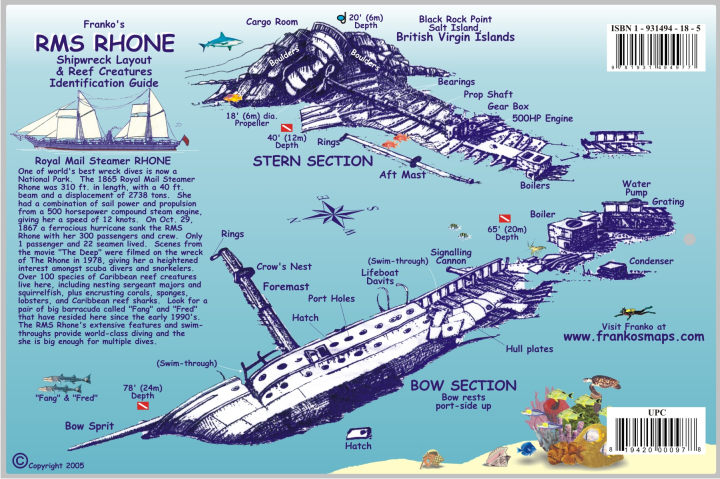

However, just as Rhone was passing Black Rock Point, less than 250 yards (230 m) from safety, the second half of the hurricane came around from the south. The winds shifted to the opposite direction and Rhone was thrown directly into Black Rock Point. It is said that the initial lurch of the crash sent Captain Woolley overboard, never to be seen again. Local legend says that his teaspoon can still be seen lodged into the wreck itself. Whether or not it is his, a teaspoon is clearly visible entrenched in the wreck’s coral. The ship broke in two, and cold seawater made contact with her hot boilers which had been running at full steam, causing them to explode.

The ship sank swiftly, the bow section in 80 feet (24 m) of water, the stern in 30 feet (9 m). Of the approximately 145 crew and passengers on board, twenty-five people survived the wreck. The bodies of many of the sailors were buried in a nearby cemetery on Salt Island. Due to her mast sticking out of the water, and her shallow depth, she was deemed a hazard by the Royal Navy in the 1950s and her stern section was blown up.

Unfortunately, we didn’t get to actually dive the wreck. We took the dinghy over from the boat, tied it to the mooring line, and jumped on in! We all had fun seeing how far down we could swim (mostly for pictures). It wasn’t really too crowded even given how popular a spot it is!